Sometimes when I’m in a tall building or a plane, I wonder how far away the horizon is.

Well, at least I do during days of better air quality and clearer skies…

Or if there’s some mountain or something in the distance I’ll wonder how far away from it you can go and still see it before the curvature of the Earth hides it below the horizon. It might seem like a tough problem to solve since spherical geometry is a notoriously difficult aspect of university mathematics, and we’re talking about distances relative to a curving Earth. It turns out, though, that it’s really not so bad! The only math you need is middle/high school geometry.

Suppose your eyes are elevated above the surface and you look out towards the horizon. The collection of all points you can see form a circle like so:

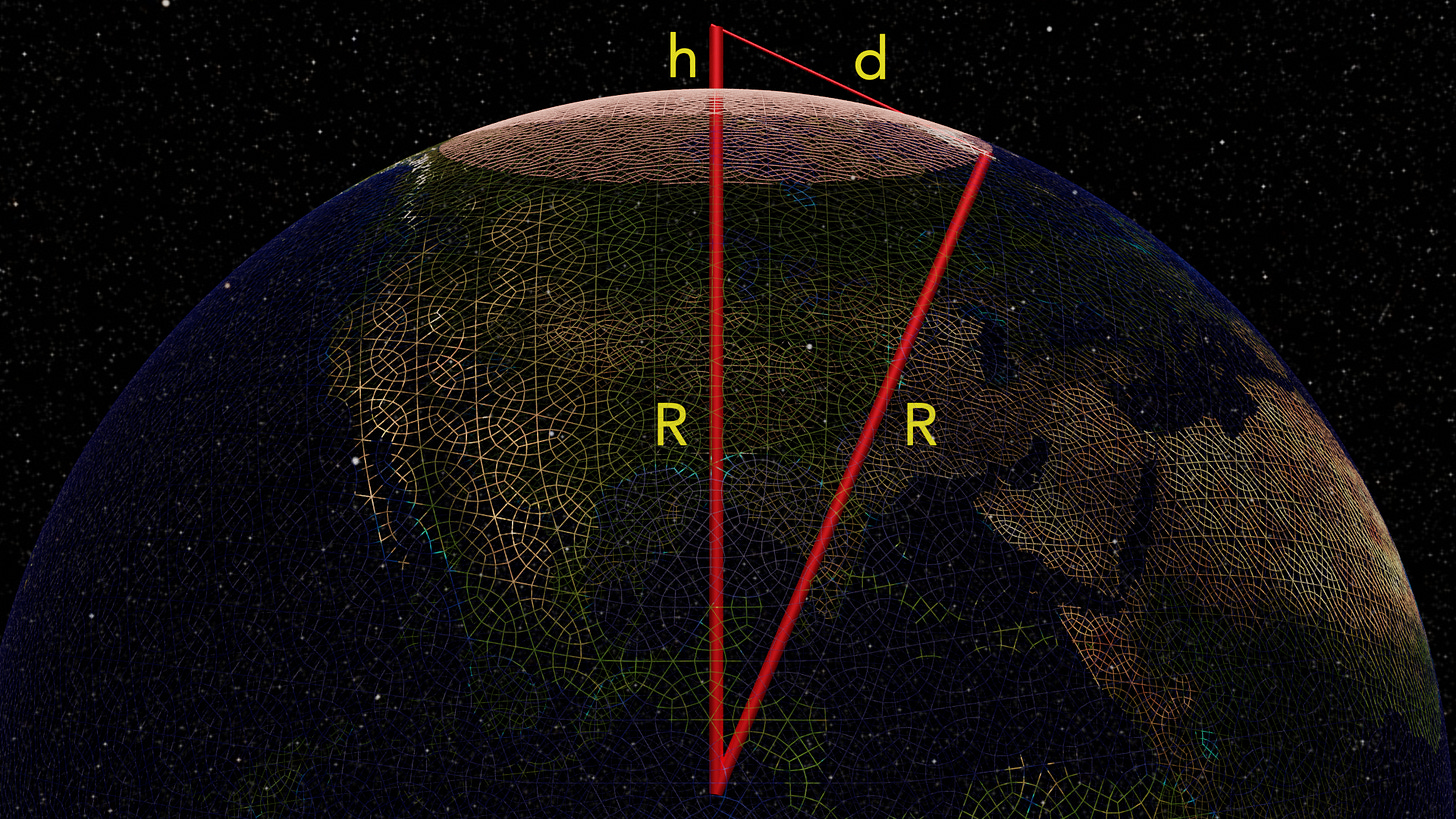

The outermost edge of the circle is where your sight line is tangent to the Earth — it touches the Earth at just one point. Now one result from geometry is that the tangent line makes a right angle with a line down to the center of the sphere (the radius). Seen from the side of a see-through, webbed Earth, we’ve got this:

Well, if the angle between d and R is 90 degrees, then that red triangle can be solved with good ole Pythagoras:

What we’re really interested in is that distance to the horizon d, so

And that’s it!

Ok, let’s try it out. Everything there is a distance, so the standard scientific unit for that is the meter.

If you’re a person 2 meters tall (h) and the Earth’s radius is 6380 km (R, and remembering to multiply that by 1,000 to change to meters), then

or about 3 miles — that’s the distance to the farthest point you can see if you’re, say, on the beach looking out to the ocean.

How about if you stand on your roof (10 meters high)? Then you can see more than twice as far:

or about 7 miles. But look, that calculation is really a bit more complicated than it has to be! Writing out each term,

carrying out the calculations to a ridiculous amount of precision. But the point is that adding the “100” to almost 128 million inside the square root really doesn’t make any difference. If we neglected that term, we’d have

For a theoretical difference of 4 millimeters. So for any normal situation close to the Earth’s surface, h is a lot less than R, and we can forget about that term:

Back up to that first image! If you’re on the Empire State building’s observation deck (h = 320 meters high), then that horizon is about 64 km away, or about 40 miles. Noice!

Now, if we want to know orbiting satellite horizons (which is a real thing that people who design and run satellite constellations want to know) then we’d want to use the exact equation since that height above the surface is not much less than R. Suppose you know that a particular satellite orbits 4000 km above the surface of the Earth and it just rose over your horizon. Then you know that it’s

or just over 5,000 miles away.

Great! Let’s do something just a bit more complicated. What if you’re observing some distance above the ground and looking at something that is itself above the ground? It turns out that this is pretty easy! In order to just see the top of the thing, you need the sight line between the two heights to just touch the horizon. But look — that’s the same as saying that we’d just add the horizon distances for each!

So the last thing is just to leave you with something to put in the back of your head: all of us who use the crazy U.S. units of feet and miles, here’s the version of the quick formula for us: changing the observing height to feet and converting the final distance to miles, we have

So plugging in 1,050 feet to the Empire State example, we get about 40 miles, as before.

Well, actually…

Ok, just to be a bit more realistic, it turns out that the atmosphere bends light a bit, so things that have disappeared below the horizon (their straight-line light paths are above your eyes) can actually still be visible if the light is bent down towards you. The simple correction for this actually works pretty well, and amounts to about a 8-10% increase in horizon distance:

So looking out of the window on a plane cruising at about 35,000 feet, on a clear day, your horizon is about 250 miles away!

On Deck:

For next time:

People come up to me on the street, all the time, even tough guys — big tough ones, tears in their eyes, they say “Sir, I keep looking all over the place for fun articles on cubic binomials but can’t find any. Could you please help us, sir?” We love the cubic binomials, don’t we folks? Not the quadratic ones, they can go to hell, but the beautiful cubics. The best binomials, really. We’re gonna do them next time. We’re gonna do them so nice nobody’s going to believe it.

If you’re a student/teacher and want to see lots of worked examples/derivations that I like to include in my classes when I teach the “standard” University Physics 1 and 2 courses, feel free to browse the (growing) collection of 150+ videos at

This publication is free to all; if you’d like to support it, though, or if something is especially cool and you’re inclined to leave a “tip”, I don’t consider myself above taking coffee or pizza donations (the very fuel of ideas!): In fact, following Douglas Adams, I’m not above accepting coffee or pizza in the same way that the sea is not above the clouds.

Thanks for reading First Excited State! Subscribe for free to receive new posts automatically!

when i was in paris with my parents in 8th grade, i was taking geometry, and one of my fondest memories was doing some napkin-math at a little cafe with my dad one evening to determine the distance we were from the Eiffel Tower based on the few numbers we did know about it... this reminds me of that