Happy Birthday to Me! (I mean, this Blog)

Today, together with yesterday, marks a very special Anniversary Double Issue of FES, doubtless a moment to be relished by future collectors of this publication. April 1 2022 saw the birth of First Excited State; I fully expected to top out in the high single-digits in terms of subscribers; to my utter surprise this little plucky blog serves in the low-to-medium triple digits a year later. I deeply appreciate all the comments and encouragement over the past year, and hope to keep finding things that pique my interest and hopefully yours as well from time to time. Break open the piggy bank here in the FES office complex! Let there be cake for all the staff!

You’re Tearing Me Apart

Suppose you’re attracted to another body, but you find that if you get too close, you wind up getting ripped apart.

[…]

Anyway, if we’re talking about a moon held together by it’s own gravity, it turns out we can calculate this distance of closest approach. Here’s how we do it: let’s consider a little rock on the surface of an orbiting moon m (radius r) closest to the large attractor M having a radius R (we’ll call this test mass u).

We have to figure out what happens to that rock as the moon m orbits closer to M. Newton told us how to calculate the gravitational force on the moon and on the rock; they depend on the distance from the planet, but we have to notice that the rock is slightly closer! So the forces look like

It might be easier to think in terms of accelerations (the force per unit mass!) so we don’t have to worry about the different masses m and u:

Now the subtle thing is that these accelerations will be a bit different because of those different distances. It’s that difference in accelerations that will cause the rock to separate from the moon a little bit, since the pull of M on the rock is slightly bigger than the pull of M on the moon:

Well, that’s messy. But now we pull out one of the favorite physicist tricks: approximations! Thinking about most realistic planet/moon systems, the distance d from the planet to moon is way bigger than the size r of the moon itself. So comparing terms separately in the numerator and denominator, anything involving an extra power of r is going to be very small, so we get (approximately!)

Now, this is the extra little bit of acceleration that is stretching the moon out, and it’s countered by the cohesive effect of the moon’s gravity trying to hold itself together. The interesting limit is where these two things just balance:

So this is the Roche Limit — inside of this distance, an object held together only by it’s own self-gravity will start to disintegrate! By the way, why don’t you, dogs, and baseballs disintegrate? Because you’re held together by molecular bonds, not just the mutual gravity of all your parts.

Sometimes you see this written in a slightly different way. It turns out measurements in astronomy are tough, especially so for little objects like moons; here, it looks like we need to measure M, m, and r. It’s often easier to just approximate the density for each object:

That’s how it’s usually written. It’s also cool to think about some limits of this: we wouldn’t have to worry about a moon’s disintegration if the Roche Limit is less than R, or inside the larger object itself! Just playing with the algebra, we get d=R when the massive object is about half the density of the satellite. So, for example, we don’t have to worry about any of the rocky planets getting torn apart by the Sun since their average densities are something like 4 or 5 times larger than the Sun’s.

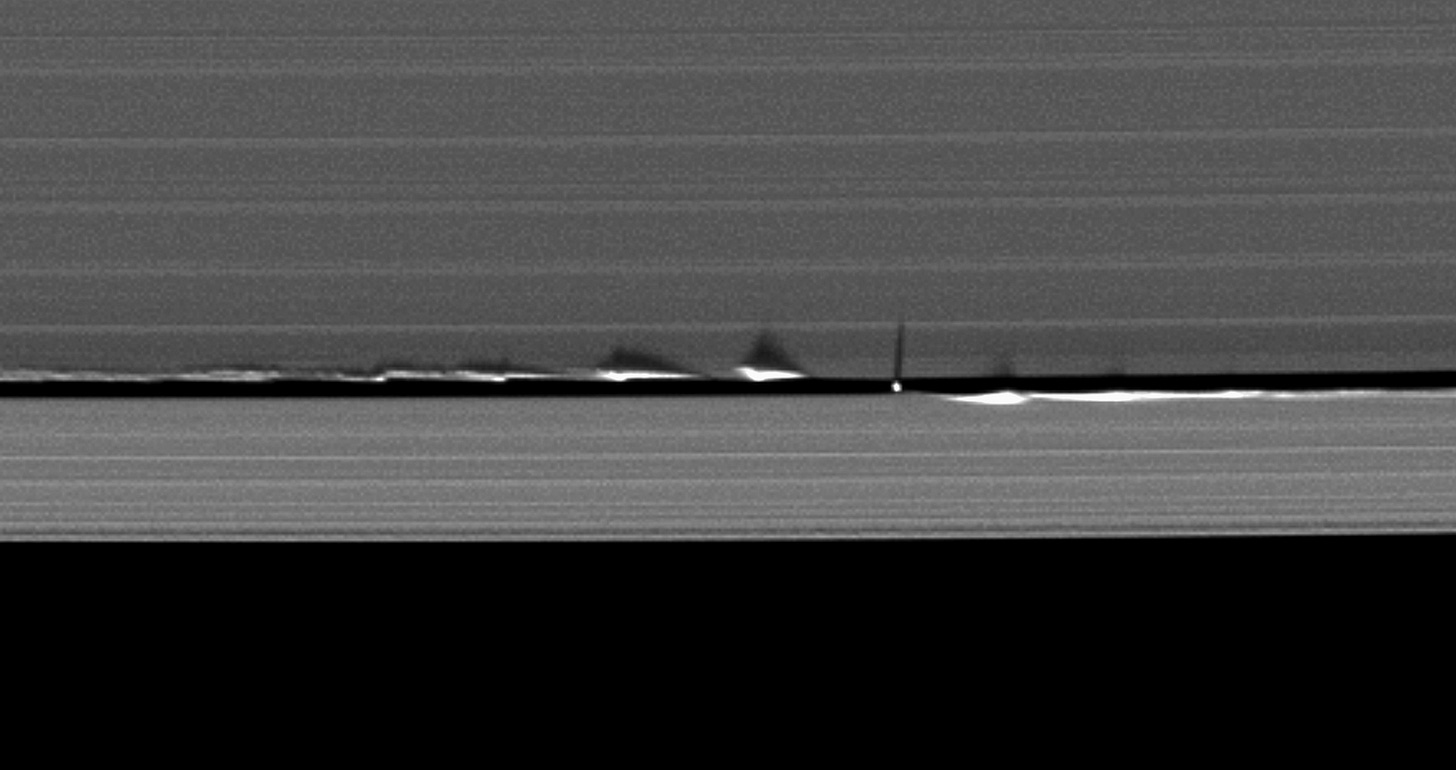

Many of Saturn’s moons, on the other hand, are fairly close to their Roche Limits, lending credence to the idea that Saturn’s rings might have formed (or are still being fed) by the continuing breakup of those icy moons. And just because I think it’s one of the coolest images ever taken, here’s a tiny moon Daphnis bobbing up and down in its orbit around Saturn, inducing waves in the surrounding rings

Slightly better result!

We can do a bit better than the above. “Real” moons will stretch a bit as they get close to their Roche Limit, which alters the calculation. And, let me say, alters it in a way that is significantly harder to analyze, at least for this ole blog. Making the moon more “fluid” changes the number out in front from 1.26 to 2.44, so maybe it makes sense that the disintegration radius is somewhat bigger in reality. There is something we can do, though, to make things more realistic — moons usually spin! And, also usually, they’re tidally locked to their planet (like ours), so one rotation about their own axis is the same amount of time as an orbit around their planet.

Let’s put that in, just for kicks. If the planet is spinning counterclockwise in the sense of the first diagram above, then our little rock feels an additional acceleration due to the spin, so we’ll add a term

into the acceleration-balance equation earlier. You can trace through the algebra, but notice that this term is almost the same as the acceleration difference δa from earlier; we only need to change the 2 to a 3. So instead of 1.26 out front, now the Limit has expanded a bit to 1.44 if the moon is spinning. Kind of makes sense, really, since it seems right that if you’re a little rock on the moon it’s easier to detach you from the surface if you’re also spinning around.

Finally, maybe the version that’s of most use to astronomers involves the fewest quantities we’d actually have to measure! We’ve got two things involving the large mass there, density and radius, and they’re related by the mass of the planet. So, at last, here’s about the simplest version I can cook up:

So all we have to know is the mass of the large object (which is usually easy to calculate if we watch the orbit of the moon) and some guess at the density of the moon.

Happy Moon Ripping!

On Deck:

For next time, I’m working on an article describing an astonishingly successful and simple tool in a physicist’s toolbox: Dimensional Analysis! And not just using it to convert between systems of units, but to guess at the form of complex equations. It seems to work way better than it has any right to!

If you’re a student/teacher and want to see lots of worked examples/derivations that I like to include in my classes when I teach the “standard” University Physics 1 and 2 courses, feel free to browse the (growing) collection of 150+ videos at

And if something is especially cool and you’re inclined to leave a “tip” I’m not above coffee or pizza: In fact, following Douglas Adams, I’m not above accepting coffee or pizza in the same way that the sea is not above the clouds.

Thanks for reading First Excited State! Subscribe for free to receive new posts automatically!