Visual Proofs

Math *can* be beautiful...

Ok, so I love proofs. I think, really, it’s that I love the absolute certainty of them. The initial assertion is incontrovertible and unassailable, and if you disagree with it, you’re simply wrong. Wow! I remember reading a favorite textbook whose author apparently loved the phrase “we are forced to conclude that…” and I always felt a little internal bristling at that. Don’t tell me what to do!

It turns out that proofs aren’t really used much outside of formal mathematics and logic. It’s a popular misconception that science or the scientific method “proves” some idea to be right. Science is an inductive process: we try to generalize particular observations to support a model that explains all such observations. Even Newton’s Laws (they’re called Laws, for heaven’s sake), assumed to be accurate models of Nature for hundreds of years, were shown to be inaccurate on very small (atomic) scales as well as for objects traveling fast (close to the speed of light). Mathematics, on the other hand, is more like a deductive process, where each step necessarily follows from the former one.

Here’s something most everyone has seen:

There are, for sure, sets of numbers you can come up with that will satisfy the equation. The most famous “Pythagorean Triple” is a=3, b=4, c=5. There are lots of others too:

It’s not obvious, though, that these numbers correspond to the legs of a right triangle! It turns out there are many ways to prove that this is the case, but many of these ways are really only accessible to folks who have

some familiarity with mathematical language and prior theorems

patience

Enter “visual proofs”! Sometimes a little image or animation can illustrate a complete proof. Here’s one (you can construct it yourself on graph paper) for right triangles:

Make a square 5 units on a side, and then divide the sides up into triangles having legs 3 and 4 units long. Then you verify the thing in the middle really is a square with an area of 25. Ok, here’s the tricky bit — now imagine sliding the opposite triangles together to make little rectangles. That leaves two squares, one with area 9 and one with area 16. Because the rest of the area is just those little triangles, it must be that those two squares together are the same as the 25-unit area we had earlier.

But I think this is an even better one:

Fib - o - natchi!!!

Sometimes beautiful mathematics blossoms out of innocent play. Suppose you were doodling on a piece of paper, just starting with 0 and 1 and adding them together to make the next number: 0 + 1 = 1. Then you take the previous two, add them, and get the next one: 1 + 1 = 2. And so on:

2+1 = 3

2+3 = 5

3+5 = 8…

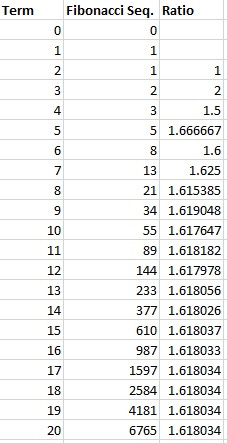

These are the Fibonacci numbers! So easy! And it turns out that these numbers have cool properties that aren’t immediately obvious. If you take one of these numbers and divide it by the previous one, the ratio you get between them tends towards a certain (irrational) number, about 1.618 (called “phi”). Phi has been exhaustively studied, pops up all over natural structures and human aesthetics, and is nicknamed The Golden Ratio

Another really neat (and for sure not obvious) property is that if you add up the squares of the first, say, 7 Fibonacci numbers, that will equal the 7th times the 8th number:

1+1+4+9+25+64+169 = 273 = (13)(21)

Mathematically, in general, that would be

It’s one thing to see this written out mathematically, but it’s quite another to see it:

Adding up all those squares really does give you the area of the rectangle! And it’s only visually that you start to see the overall design of the set of numbers — tracing out a curve smoothly hitting the opposite corners of each square reveals the Fibonacci Spiral, a shape approximated often in Nature on many different scales.

Binomial Expressions

Every student in algebra, at one time or other, gets tripped up by “expanding the square of a binomial”. If you’ve got (a + b), what happens if you square that sum?

At some point, whether it’s from hurrying or just because it feels so dag-gone right, everyone will do the first (NOPE) thing. The second line is right, but why? I mean, you can plug in some values and see that it has to be right

but seeing it visually really tells you why that extra funky 2ab term needs to be there:

The whole square has an area of (a+b) squared, so you need all those pieces for it to work out.

Noice.

The visualization for that expression is pretty easy to generate since squares are 2D. What happens if we cube the binomal? There’s a way to generate the expansion for any power you like, but it gets complicated quickly. Here’s what it looks like for the cubic:

Yuck. But in 2D each term had a geometric representation (the area). In 3D, then, you might expect each of those terms to represent some kind of volume. So I messed around in Blender (the free 3D software) and tried to see how to assemble the whole volume from the volume of each term. And it works!

I used a=3 units and b=2 units, so the overall cube should be 5 units on a side. If you watch it a couple of times, it’s cool how the whole cube really is built from each term. The above thing is a GIF; if you want to see it as a video you can pause and link to (because this is going to blow up the internet!) here it is on the YouTubes:

On Deck:

For next time: I spent some time ragging on Newton’s Laws as not being “correct”, but next time Imma dig in a bit and show just how powerful they actually are — the same rules explain both the motion of a mass on a spring and the planets orbiting the Sun.

This publication is free to all; if you’d like to support it, though, or if something is especially cool and you’re inclined to leave a “tip”, I don’t consider myself above taking coffee or pizza donations (the very fuel of ideas!): In fact, following Douglas Adams, I’m not above accepting coffee or pizza in the same way that the sea is not above the clouds.

If you’re a student/teacher and want to see lots of worked examples/derivations that I like to include in my classes when I teach the “standard” University Physics 1 and 2 courses, feel free to browse the (growing) collection of 150+ videos at

Thanks for reading First Excited State! Subscribe for free to receive new posts automatically!

i LOVE this post... i think this is the exact reason i find calculus to be the most satisfying math... the “ah-ha” moment from doing riemann sums and then learning integrals was blissful

So true, that in science we almost never know anything for certain. I like the phrases “the data support the conclusion that…” or “I am persuaded by the evidence that….” That leaves the door open to new evidence, or as I once heard a leader in my company say, “we reserve the right to get smarter tomorrow.”