Well, my personal news is that I’ve changed careers — after 20 years I’m no longer in the classroom! Ready for new problems to solve, I’m now doing data analysis and climate research. One consequence is that I’ve got crazy large weather/climate databases lying around, so I thought I’d dip into it a bit by talking briefly about a couple of really common (bad) arguments against global warming:

“We can’t even predict the weather very well a week out, how can we possibly know what’s going to happen in 2 decades?”

“There’s been no warming in the last x number of years, I thought the temperature was supposed to, you know, warm up?”

The answers to these are really sort of tied together. Check it out — here were the temperatures during a week or so in my local neighborhood back in March 2011:

The 6 or so little peaks aren’t hard to understand — it’s usually warmer in the daytime (the dates are UTC). Now, why do they have the specific values that they do? Any particular day’s high and low is influenced by a great number of things (fronts, cloud cover, humidity, storms…) that really are hard to predict well more than a few days in advance. And, looking at this thing, it’s not hard to argue that the overall temperatures maybe got a bit cooler at the end of the week compared to the beginning. Maybe.

Here’s the point, though: given the first plot showing (slightly) decreasing local temperatures, I can still tell you confidently that 4 months later the average temperature would be higher! “Of course, dummy, it’ll be summer.” Right. But there’s a subtle point here: during that week, it was getting closer to summertime, and yet it was cooling. It’s possible, in the short term, for fast-timescale changes to mask the much slower change going on underneath. What is that slow change? The tilt of the Earth, of course!

That tilt has consequences: as the Earth orbits the Sun

sunlight is hitting the surface more directly (more efficiently heating the surface), and

the days are getting longer, so there is also more time during the day for heating

The point is that the phenomenon responsible for my confident forecast has nothing whatsoever to do with the phenomena responsible for day-to-day forecasts! And it’s way simpler to model.

Sure enough, in what will surprise absolutely no one, it was indeed hotter that summer than it was in the springtime:

Now, a similar thing is going on with the global climate. Here’s a plot of the global average temperature for about a decade:

What influences that? Typically, an even more bewildering array of numbers (solar radiation received, cloud cover, ocean cycles, atmospheric composition changes…) that are all changing day-to-day. And again, as suggested by the green line, you could reasonably argue that the global temperatures got a bit cooler over that decade.

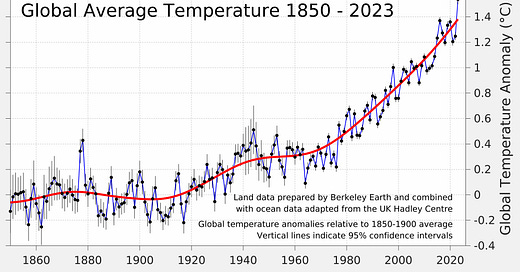

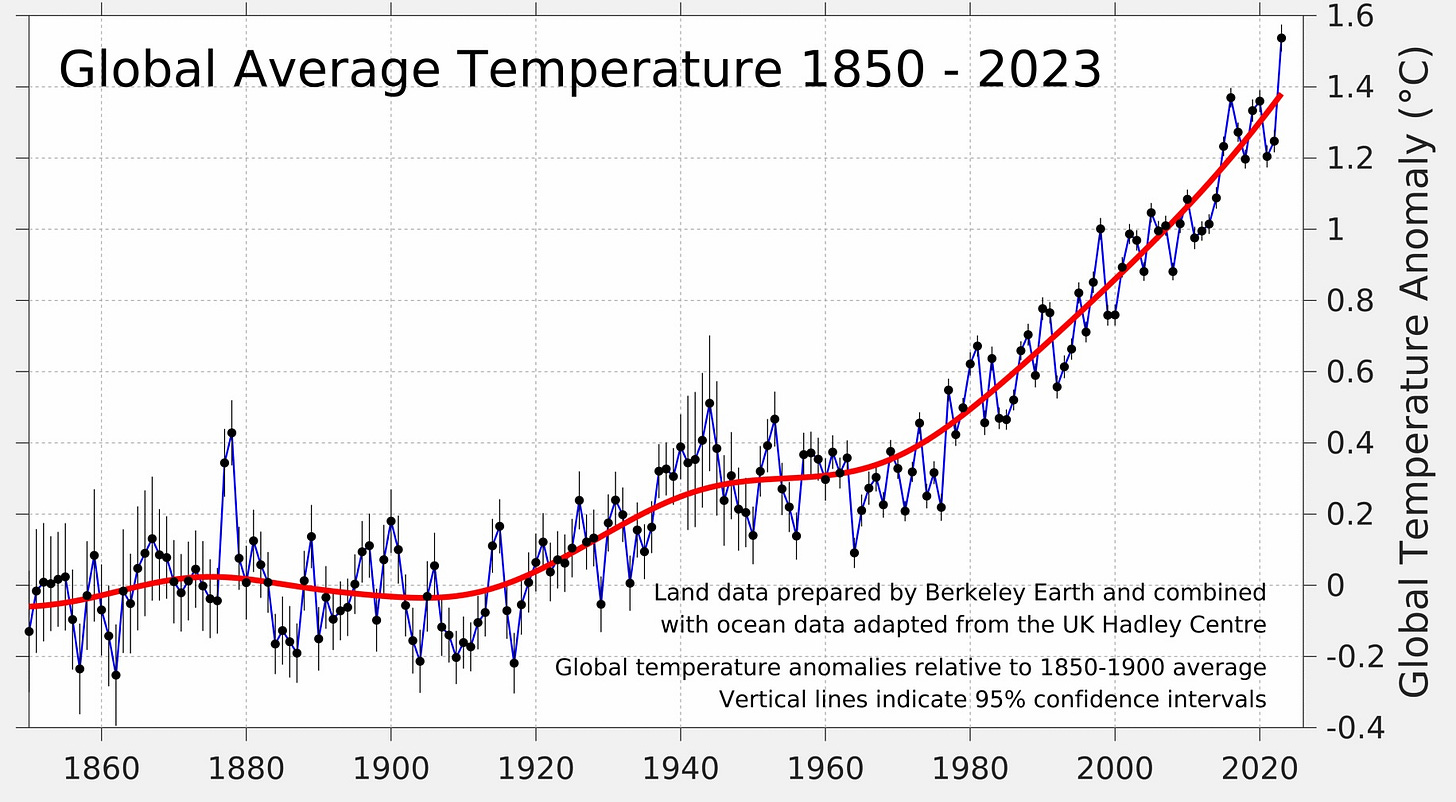

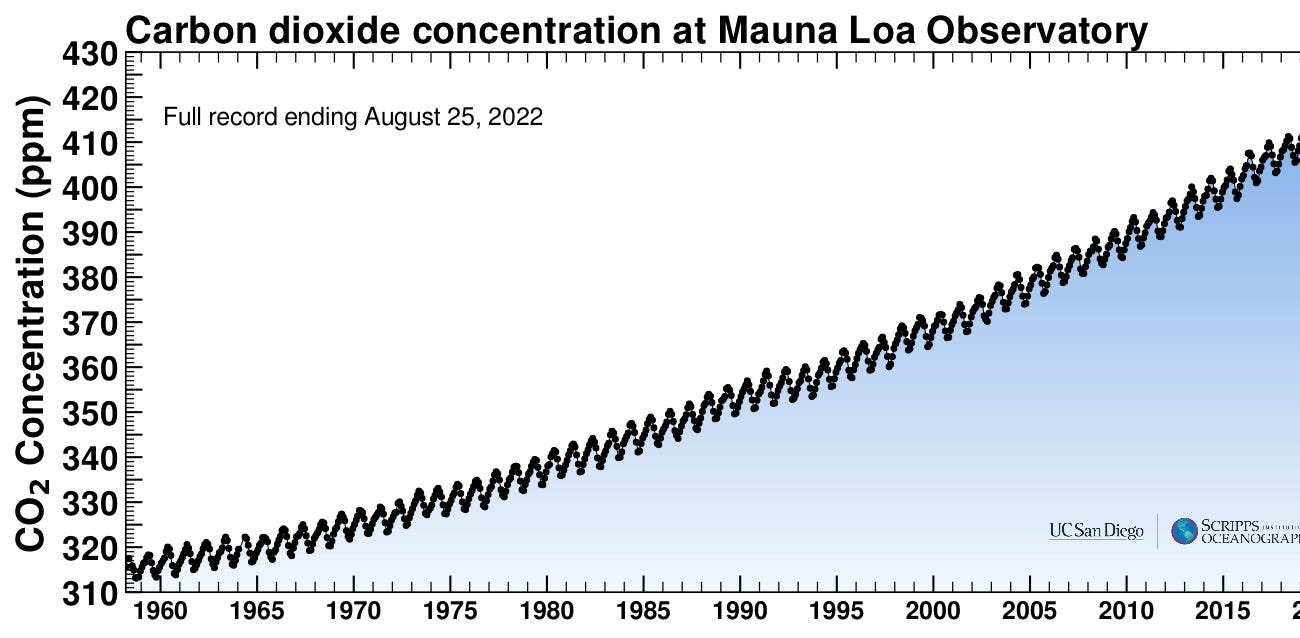

But is there a slower, subtle change going on underneath that? Yep — it’s the accumulation of increasing amounts of carbon dioxide, which warms the surface. It’s hard to see the effects year-to-year, but the inexorably cumulative effect is obvious when looking at the long-term trends:

So: just as the slow buildup of heating effects seasonal changes in temperature, even though you might have week-long cold spells in the other direction, the global climate might cool for a bit in the short term, only to be nudged ever higher in the long term.

The initial arguments above against global warming are bad arguments because the reasons for long-term temperature increase have nothing to do with the reasons for the short-term changes; and, in fact, they’re way simpler.

For more on the tie between carbon dioxide and temperature change, check out

Human-Caused Global Warming? Yep.

Here’s the pretty simple and hopefully convincing case that humans are responsible for the recent warming of the Earth. I’ll identify 4 steps in the chain of reasoning:

On Deck:

For next time: I kinda don’t know! There’s a particular book project involving popular-level astronomy I’ve been itching to get started on, so perhaps I’ll be drafting chapters and giving them a test drive here…

This publication is free to all; if you’d like to support it, though, or if something is especially cool and you’re inclined to leave a “tip”, I don’t consider myself above taking coffee or pizza donations (the very fuel of ideas!): In fact, following Douglas Adams, I’m not above accepting coffee or pizza in the same way that the sea is not above the clouds.

If you’re a student/teacher and want to see lots of worked examples/derivations that I like to include in my classes when I teach the “standard” University Physics 1 and 2 courses, feel free to browse the (growing) collection of 150+ videos at

Thanks for reading First Excited State! Subscribe for free to receive new posts automatically!

Congratulations on breaking free from the chalk face! I hope you enjoy your new job, as much as I enjoy your posts 🥰