Old Stuff

Does the Earth go around the Sun? Duh. It’s common knowledge, to the point where people that say otherwise are thought of as only just slightly above, say, flat-Earthers1 with respect to the Modern Science Catechism. But while most people could think of fairly obvious observations or experiments that could demonstrate a spherical Earth, just how would you try to convince someone that the Earth actually spins on its own axis and orbits the Sun (a heliocentric model)? It’s actually kind of a tricky business. So tricky, in fact, that it was only in the last 400-ish years that we could really rule out the old geocentric model that was the common sense up to that point.

Here’s basically what happened:

Ok, first, a universal procedure in science is to build a model in an attempt to explain some phenomenon and then modify it as needed once longer and/or more detailed observations are made. I like to use this word “model” instead of “theory” since it kind of implies a temporary human construction. Let's try this in trying to explain the motion of objects in the sky -- in this way we'll also be (in a very simple sense) retracing the efforts of people over thousands of years to develop a cosmology, a robust and consistent explanation of how the Universe as a whole works.

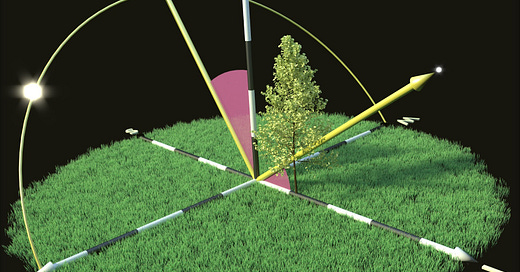

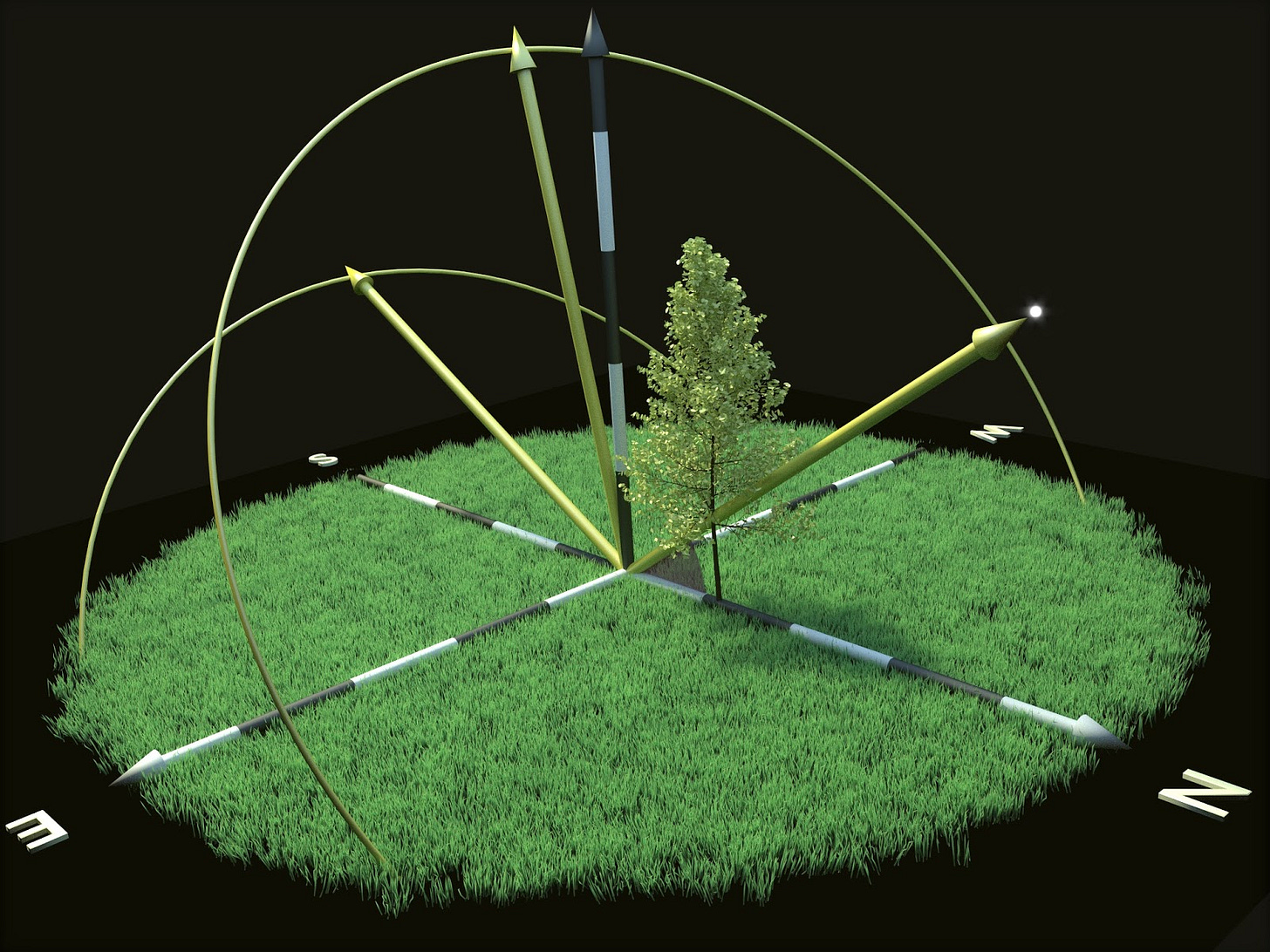

To start, a simple observation is that the Sun rises in the East and sets in the West (roughly) — most days aren't exactly like this, but in “toy” models we make many simplifying assumptions and then slowly generalize to the “real” case after we think we understand things. Now let's suppose you're in the Northern Hemisphere in the middle of the United States. If you keep track of the Sun's position in the sky during the day, you'd see something very much like the above illustration. Notice, for example, that the Sun doesn't climb directly overhead (this overhead direction is called the zenith) but traces an arc across the sky that is always somewhat south of the zenith. In fact, if you were very careful in your measurements, and if you were able to turn off the pesky blue glow of the atmosphere in order to be able to see stars during the day (yes, they're there all the time, and they rise and set!) you'd see that the southerly angle of the sun at noon is about the same as the "elevation" of a certain famous star above the horizon, although this changes with the seasons — that’s illustrated here:

I made a quick animation of the idea:

Notice that the stars move much as the Sun does, but there’s an interesting pattern --- only some of them seem to rise and set. There are others towards the north (for example, the Big Dipper in the Northern Hemisphere) that trace little circles around the “North Star” (Polaris! It’s a supergiant 30 times larger(!) than our own Sun and is the boss member of a triple star system). After watching this motion for a while, you might convince yourself that the Sun, Moon, and stars in the heavens seem to be glued to a great dome that rotates around us, where the axis of the dome points very nearly at Polaris. As this pattern seems to repeat itself daily, let's propose this to be a first cosmological model. So far as we’ve observed, it explains how the Universe behaves.

Now, the way science operates is that we should try to imagine consequences of the model, or predictions that it makes that we could check. For example, if all the heavenly objects really are just firmly affixed to the rotating sphere, the Sun ought to rise and set at the same point every day. Maybe this appears to be true to your naked eye for a few days, but if you carefully record the position of the rising and setting sun you'd notice that it changes slowly as the year goes by. The Sun in the wintertime (for those of us in the Northern Hemisphere) rises noticeably further to the south than it does in summertime (like in the above image). The stars do not follow the same pattern so it cannot be true that the Sun is "stuck" to the cosmic dome in the same way that the stars are. It’s also readily apparent that the Moon changes position (and phase!) from one night to another. And in kind of a surprise to most people, there are other lights in the sky that follow strange patterns of movement relative to the stars if we carefully observe them over a long period of time: these we'll call planets, from an ancient word meaning "wanderer". As an example, watch the path of Mars over a few months:

If you were to look at the same patch of sky and take a picture of the position of Mars every night from May 1 to Nov. 1 in 2018, you'd see Mars trace out a surprising loop as the weeks go by. As the video shows, Mars initially appears to move across the sky relative to the stars steadily, and then start moving backwards for a time, then continue roughly in the original direction again. This apparent backwards motion (which happens for each planet) is called retrograde motion.

Well, obviously our simple “lights stuck to a dome” initial model needs to be revised (this is exactly the process of science!). Sometimes we’re lucky and a spark of imagination occurs to someone whereby a truly new and simpler model is able to explain the new as well as the old data. The usual way of modifying an existing model, though, is to add just enough new complexity to explain the new observations while still remaining consistent with all prior observations. For example, our first simple model had all the heavenly objects stuck to a single rotating cosmic dome; an easy modification would be to suppose that each object that moved in a "weird" way might move on its own independent sphere (and all of these spheres would obviously still rotate around the Earth). But how to explain the retrograde motion? The prejudice of the time was to assume all heavenly motion was perfect, which meant to them that all motions must be circular and uniform (not changing in speed). It's obviously difficult to account for the backwards motion of the planets if their speeds are constant! The clever solution goes like this: What if Mars, for instance, traveled on a sphere (an epicycle) that rides along on another sphere! (called the deferent) This combined motion can be made to reproduce the observed loop as shown above without violating the above assumptions --- all motion is circular and uniform, as long as the added complexity of more spheres is still palatable. Tricksy! Here’s an animation of it:

Note in the little movie that the arrow representing our sight line to Mars will temporarily move backwards from time to time just like the "real" motion as seen from Earth. Genius! Cool, so now every object that exhibited retrograde motion was said to rotate on its own epicycle. It’s a messier model, but pretty accurately described the apparent motion of the planets!2

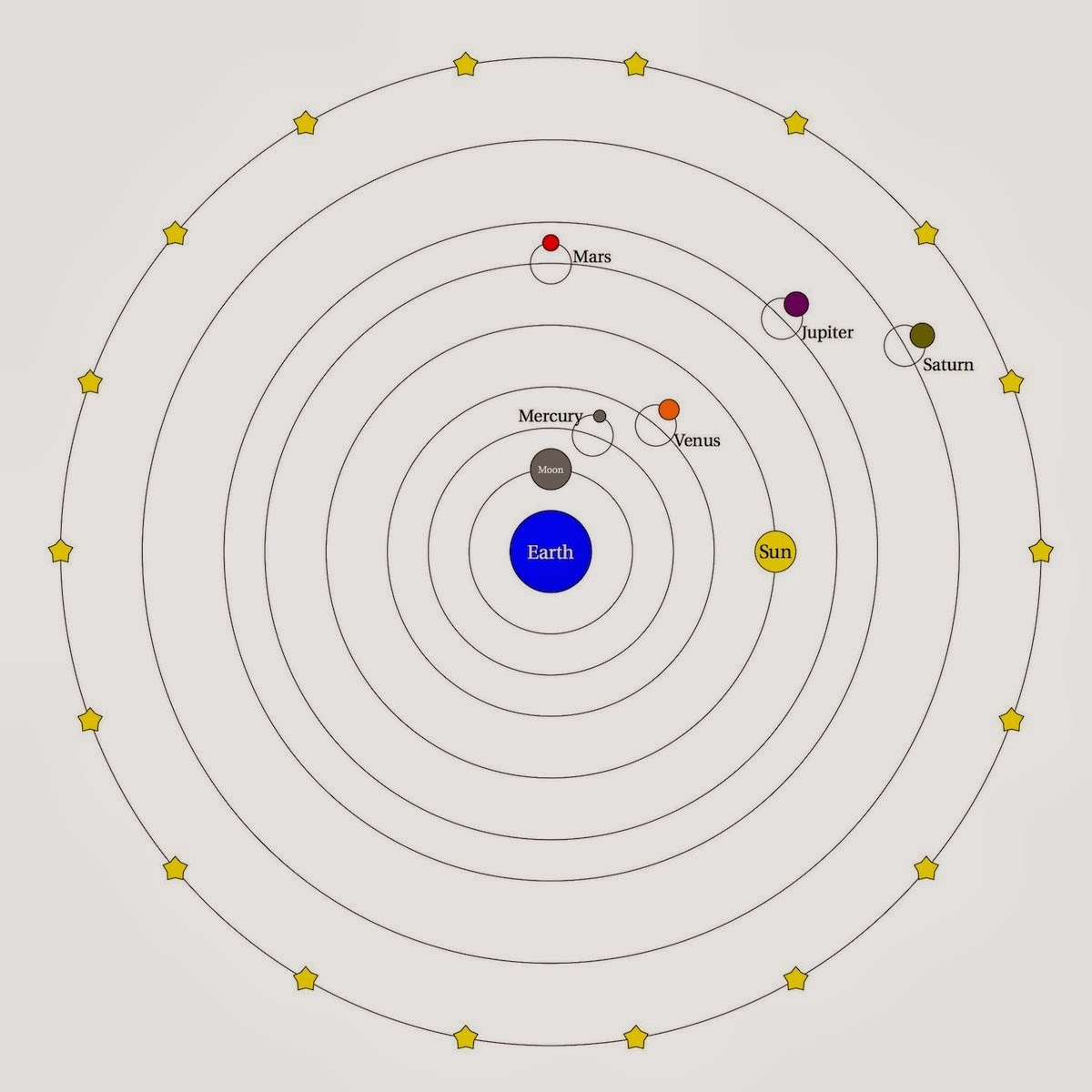

The eventual model had, in outgoing order, the Moon, Mercury, Venus, Sun, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and the "fixed" stars, each on their own sphere rotating around the Earth. Additionally, as we've seen, it's necessary to put all but the Moon, Sun, and stars on additional epicycles to account for the observed retrograde motion.

You can see the importance of imagination in science --- it's difficult to create some new model that still can account for all known observations. Science is rarely a process of deduction, where a conclusion logically follows from some set of premises; instead, it is often inductive, where we try to take a creative leap to a new idea and concoct experiments that may provide evidence for or against it. This geocentric model was a successful explanation of how the Universe worked for about 1,500 years(!) until significant pieces of evidence obtained through careful observation overruled it in favor of a new heliocentric model…

New Stuff

Let’s fast-forward to Galileo. Up to this point we used only the acuity of our eyes to make and record observations, but now Galileo introduced the telescope as a technological advance to improve our “seeing”. The improvement in our observations was as immediate and similar to the first use of a microscope to unlock entire new worlds of exploration.

He was the first human (as far as we know) to see delightful surprises:

sunspots (the Sun wasn’t “perfect”, but had blemishes)

the band of faint light in the sky, the “Milky Way”, was actually made of millions (billions) of distant, individual stars

Jupiter was the center of its own little system of (at least) 4 moons seen to orbit it and change positions each night

the Moon was a world, a great rock, with mountains and craters

But the one I want to highlight is the Phases of Venus. When you look at Venus by eye, it’s a beautiful, warm, steady beacon of light. Through a telescope, though, you might notice that Venus isn’t just point-like or a disk:

Maybe surprisingly, this wouldn’t be a surprise to a geocentrist. The old model predicts this! Check out the geocentric model scheme above — Venus always appears between the Earth and Sun, so we ought to expect new and crescent phases.

[BTW, I wrote an article on what phases are all about here]

So this in itself isn’t such a big deal. Here’s a 3D mockup of the old model:

The crucial point is that what we should not expect gibbous and full phases! I mean, it could happen in the old model, but that would mean that Venus is on one side of the sky and the Sun is on the other (180 degrees apart), and this is never observed — Venus gets a maximum of about 46 degrees away from the Sun, which would then still be seen as a crescent. But the old model was safe since Venusian phases can’t be seen with the naked eye.

So along comes Galileo with this new tool — what did he see?

The complete set of phases!!

With one set of observations, he ruled out the old model. This is an important thing — we can’t ever prove any scientific model correct, but we can surely disprove models that don’t match experiments or observations. I tried to match Galileo, so here are some images I took of Venus over a few months and rough 3D mockups of what things “really” look like in 3D:

One cool thing to notice is that the apparent size of Venus’ gibbous phase looks smaller than it does in a crescent phase, but that should make sense looking at the 3D model — Venus is closer to us during that phase, so it should appear bigger.

Here’s the full set of images I took over about 4 months:

So it really didn’t matter that a particular model was in favor for 1,500 years, or that it was the “official” cosmology of the Church, or who spoke arguments in its favor — the real test of a scientific model is whether it stands up to observational and experimental scrutiny.

The old geocentric model could not explain the easily observed, complete set of phases of Venus; the heliocentric model could, and since there currently aren’t any observations that rule it out, it’s a fundamental foothold in our current cosmological climb of understanding. Since then we’ve been able to fortify this understanding by observing the parallax and chromatic aberration of stars, phenomena that are also only consistent with the heliocentric model.

On Deck:

For next time: How far away is the horizon? Let’s calculate!

If you’re a student/teacher and want to see lots of worked examples/derivations that I like to include in my classes when I teach the “standard” University Physics 1 and 2 courses, feel free to browse the (growing) collection of 150+ videos at

This publication is free to all; if you’d like to support it, though, or if something is especially cool and you’re inclined to leave a “tip”, I don’t consider myself above taking coffee or pizza donations (the very fuel of ideas!): In fact, following Douglas Adams, I’m not above accepting coffee or pizza in the same way that the sea is not above the clouds.

Thanks for reading First Excited State! Subscribe for free to receive new posts automatically!

By the way, it's commonly thought that only during the Middle Ages was it shown that the Earth was "round" (spherical). This had actually been demonstrated a number of ways back in ancient Greek times by Aristotle, among others, but the most precise demonstration and measurement of the size of the Earth was done by Eratosthenes using a fairly simple method:

He had read accounts of the observation in a southern town that, on the longest day of the year at noon, sticks happened to cast no shadows and the Sun shone into the bottoms of wells. That would mean that the Sun was directly overhead. What set him apart from the myriad of people that knew this fact was that he had the curiosity to ask if that was true in his city of Alexandria. When the experiment was done, it turned out that at this exact time, sticks do cast shadows. This immediately convinced him that the Earth must then be spherical, and being an accomplished mathematician, a careful measure of the length of the shadow along with a knowledge of the distance to the southern village allowed him to calculate the size of the Earth to high precision (the shadow made an angle of about 7 degrees with the top of the stick, so the two places must be about 7 degrees apart along the Earth's surface; knowing there are 360 degrees around the sphere meant that they were about 1/50 of a full circumference apart, so knowing that the actual distance between the sticks was about 500 miles and multiplying by 50 yields the right answer of about 25,000 miles around).

Many people knew of this curious observation, but it is truly only the curious people that ask questions that change the world. I summarized this explanation from the lovely little vignette in Carl Sagan’s “Cosmos” series, immeasurably influential on me as a youngster:

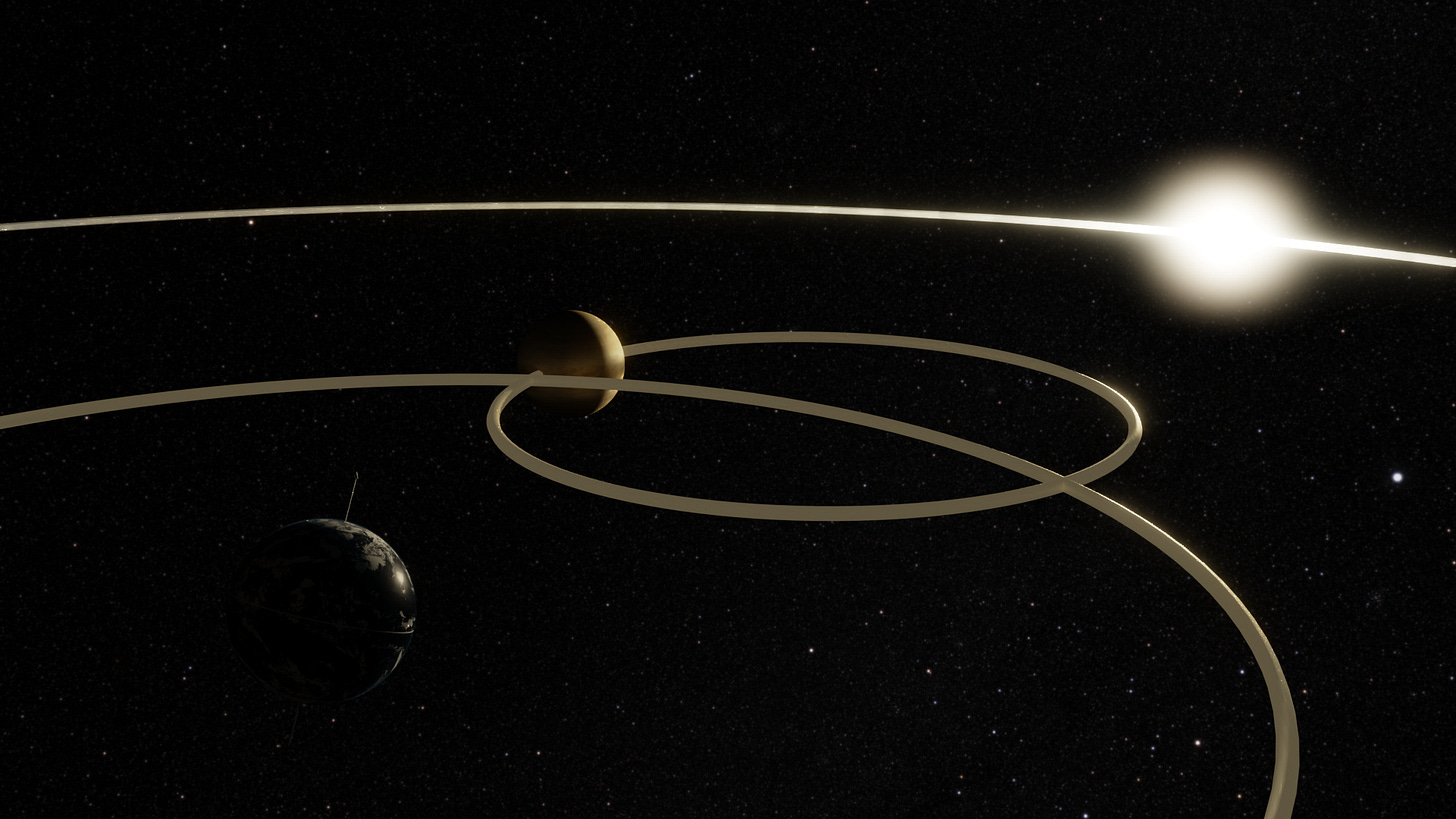

You might wonder how retrograde motion is explained by us going around the Sun — Copernicus solved this one for us. It’s cool because instead of patching up the old model with epicycles, retrograde motion is predicted as a consequence of all the planets going around the Sun (as long as we require that planets closer to the Sun orbit faster than the ones farther away, which is true). It’s just a sort of optical illusion created when we catch up to and pass a slower-moving planet in its orbit. I made a little animation of this, showing how Mars seems to move backwards relative to the Earth as we pass it: